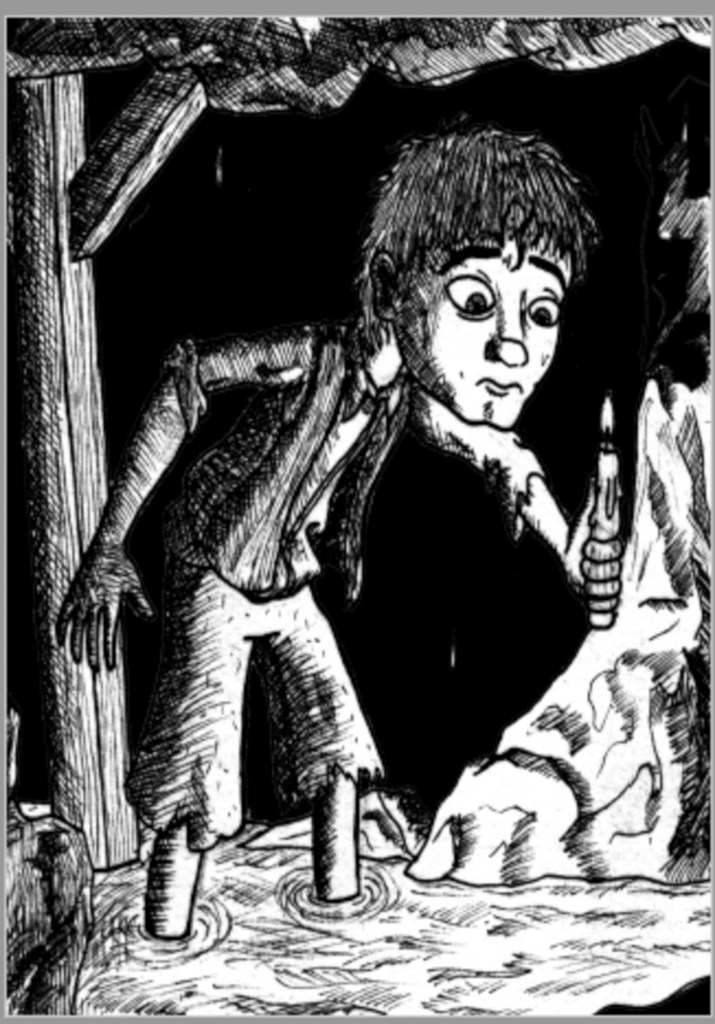

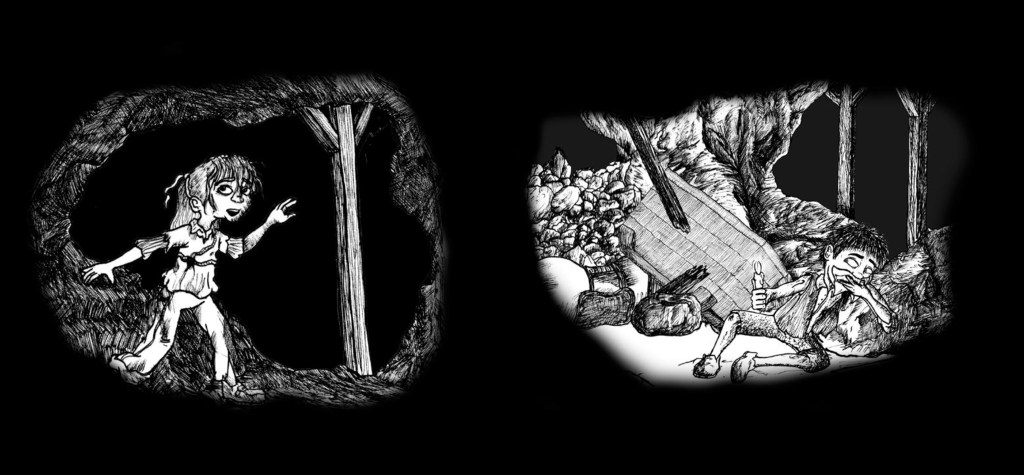

It was black, pitch black, blacker than anything he’d ever known. All around him there were groans and creaks, noises coming out of the inky blackness. He tried to stand up but

Suddenly the trap door dividing him from the rest of the narrow pit passage sprang open and something began to crawl out of the tunnel towards him. “Dad, Dad, help us, Dad,” cried Tim, sobbing as he struggled desperately to close the door, pushing hard on the soaking wood, his feet slipping in the black mud. Almost there, Tim gave one last enormous heave and the door crashed shut, in front of him.

Sobbing with relief, he leaned back against the blackened walls, blood pouring from a cut in his hands. From behind the door he could hear something shuffling around in the dark. Turning away from the door, Tim lit the last remnants of his candle, illuminating the dark passage behind him. As he raised the tiny stub, the sight in front of him was terrible: rocks and rubble blocked the passageway and just in front of him a dead rat lay crushed under a heavy coal wagon, its head lolling limply to one side. Seized with panic, Tim crawled towards it and, with the last of his strength, peered into the wagon. The stench was terrible now; a mixture of burning and rotten eggs. Blinded by the smoke Tim could just make out a dark shape moving inside the coal wagon.

“Daisy, is that you Daisy?” he croaked. Raising the candle, Tim peered inside and gasped with horror as a voice echoed through the darkness: “It’s me, Timmy, it’s your Daisy. I remembered you, Timmy – I’ve come to take you home.”

—–

“No I am NOT your Daisy,” shouted an indignant voice. “I shove harder than any girl and when I get back in that bed, that’s what you’ll be getting.” Tim looked in the direction of the voice, and there, sat on the floor was Jo, rubbing his backside and groaning.

“These nightmares are getting beyond the pale; sooner you get down that pit for real the better it’ll be for us that have to share a bed with you,” grumbled the skinny lad in the nightshirt.

A loud banging on the window made them both jump.

“Three o’clock and ready for work,” shouted the voice. “Stir yourselves, bonny lads and lasses.”

The knocking at the window grew more insistent, as Dave the Knocker Man waited to see some sign of life before he moved on to wake the occupants of the next house. “Come on you lot, shake a leg; I’ve got another thirty houses to knock up yet,” he shouted up at the window.

“All right, all right, Dave, keep your hair on man,” they heard their father shout, from downstairs.

Tim’s little sisters, five-year-old Lottie, and four-year-old Mary, were still asleep in the bed next to him, and he could just make out the shapes of his six-year-old twin brothers, Jack and Den, hiding under the covers next to him, while the two older children pulled on their clothes, shivering in the darkness of the morning.

“Come on birthday boy, hurry about it, big day today, working lad.” Jo grinned at his little brother, pulling the covers off him and giving him a friendly slap.

“You’ll have to be sharper than this when you’re opening the traps or you’ll be for it,” said Daisy with a frown.

“Hark at her, the expert,” retorted Jo. “Boss of the mine she is now, you know.”

Daisy glared at Jo and handed Tim a small package. “Here you go lad. Happy birthday, big man!” she said with a little smile.

Tim took the package, touched that his big sister had remembered. “Can I open it now?” he asked with a grin.

“No pet, keep it for later. It’s something for you when you get down the pit,” she replied.

Tim carefully placed the tiny package, wrapped in brown paper, on the table beside the bed, bracing himself to face the cold. Although the days were beginning to get warmer, the biting cold of the dark morning reminded them that winter wasn’t quite over yet. His bare feet hit the icy floorboards and he quickly reached for his woollen trousers and shift. Pulling them on, he made his way down the steep wooden stairs that led to the front room. His dad, Jay, was already up and slurping a big mug of thick tea at the kitchen table. As Tim appeared, he handed him a big mug full of the tea.

“Happy birthday, son,” smiled Jay. “Not every day you have a birthday and start work for the first time,” he said, giving Tim a playful dig in the ribs. “Looking forward to it?”

Tim tried to smile. A birthday was a big thing for a lad and normally he’d be jumping about with excitement by now. But today was different: today he’d leave the sunshine and fresh air to spend twelve hours down the deepest, most dangerous mine in the land. Today was his first day down the black hole they called the Bankside Mine Pit. He’d known for years that this day would come eventually, that the family needed the money he’d bring in. But the dream kept on coming back to haunt him. That same dream, over and over again, night after night, leaving him panting and sweating in fear. He didn’t dare tell his mum; she’d think it was a bad omen. She believed in things like that, and there was no way he wanted to pile more worry onto her shoulders.

“Of course, I’m really looking forward to going to work with you and our kid1,” he nodded, looking over at Jo. “I’ll be a real working man at last!”

Jo shook his head, muttering, “You might not be saying that after you’ve been down there for a bit.”

“You’ll be fine, our kid,” his mum interjected quickly, putting down a big jug of porridge and milk in front of them. Stealing a nervous glance at her husband, she continued. “You’re a big lad now, and there’ll be a surprise for you when you get home tonight.”

Jay’s expression suddenly darkened as he turned to his eldest son. “You don’t want to be picking up any bad habits from our Jo,” he said, slapping Tim on the shoulder. “You’ll go to work like a real man. No whingeing and whining and wanting to go stopping at home with mam and the bairns[1].” Tim glanced quickly at Jo; he hated it when his dad got at his elder brother, but everybody knew that Jo hated going down the pit. He was always skiving off with one of his heads, as he called them. Everyone knew it was just so he could stay at home with Mam.

Jo looked dejected and turned away from Tim. He’d find out soon enough, he’d soon learn what being ‘a real man’ was all about.

Tim tried to look pleased, but his stomach was turning over at the thought of what the day held in store. It would be a long time before he would be able to come home and enjoy whatever birthday surprise his mam had planned for him. Twelve whole hours in the pitch black, sat there all alone. Jay tore off a corner of the thick slice of bread and dripping that was his special treat for being the man of the house. “Here, this’ll set you up right.” The rich salty taste hit Tim’s taste buds and he savoured the moment, the rest of them looking on in envy as they ploughed their way through their thick porridge. It was a long walk to the mine and they’d need it to set them up for the day.

As the clock struck half past three, Jay took a last slurp, gave a sigh and rose heavily from the table. Moving towards the door, he took up his old coat and lunch bait, and put it in the tin that was slung around his belt. They would all eat the same that lunchtime: thick slices of bread with Mam’s strawberry jam in it. Smiling for a moment, Tim let himself remember last summer, picking strawberries then lying back on the warm grass feeling the sun on his face. There’d be none of that this year; he would spend his days, the rest of his days in the darkness, until his lungs gave out and he was an old man. One week a year holiday if he was lucky.

Jessie glanced nervously at him. She knew exactly what was going through his mind, but there was nothing she could do about it; that was his lot and he’d just have to accept it, like they all did.

“It’s thirsty work down the mine so here you go.” Handing them all two tin bottles of water, she stood by the door, giving each one a hug as they made their way out into the dark cobbled street. As Tim passed her she held out a stub of candle.

“She’ll be all right, Mam,” said Tim, trying to make her feel better. “Daisy is a tough old bird and she’s done well as a trappy lass.”

“Aye, maybe so,” replied Jessie, biting her lip; “But I remember when our Jo came home from his first day as a hurrier; he was that bad, all bleeding and sore, and his poor little head, I had to put a compress on it all night. He didn’t want to go back the next day but we made him and he was crying all the while. I don’t know how our Daisy will get on down there, she’s not over-

strong and pulling those heavy coal wagons isn’t fit work for a lass.” Mam’s face creased with worry as she looked down the street in the direction of the mine. They all knew that there was no choice for Daisy, with seven kids in the family and another on the way; they all had to do what they could to bring in a wage.

“Howay Jessie, let the lad go and stop mothering him,” said Jay, giving his wife a sharp pat, his face creased with irritation. They all had to get on with it and it didn’t help when Jessie went all motherly on them.

Turning to Tim she forced herself to smile. “Anyway pet, you never mind me. It’ll be all right, you’ll see. I’ll have you a nice dinner ready when you get home, nice bit of meat and some tatties[2] for your birthday.” Tim smiled bravely in return; he’d do anything to make her proud of him.

“Don’t worry Mam, I’ll be all right,” he said, patting her comfortingly as he moved past her into the dark cobbled street.

“Don’t forget this, bonny lad,” said a squeaky voice, and Tim looked behind him to see his six-year-old brother holding out the parcel that Daisy had given him earlier.

“Ta, mate,” he said, ruffling the little lad’s hair. “See ya marrer[3].” The younger boy beamed with delight. He worshipped Tim, always had done. Tim gulped back a tear; his little brother Jack wasn’t really like other kids, he wouldn’t understand that Tim was going to be away for so long.

Den, Jack’s twin, had understood right enough: “Off toothpit,” he’d said, smiling all over his chubby face, as he still lay cosily in bed beside his younger sisters. “Off to-the-pit.” But Jack wasn’t like other lads; he’d been all right until he was one, then his mam started to worry that he wasn’t growing like the others. When Jack still wasn’t talking by his third birthday, it was clear that there was something badly wrong with him and, as the years went by, and Den started to do the things the other boys did – climbing, getting into trouble, scrumping apples – it was clear to everyone that Jack would never be quite like other children. But he seemed happy enough, spending hours playing with the sticks and stones he collected from the fields, arranging them into patterns on the ground.

Tim tried to put them both out of his mind; he needed all his wits about him for what lay ahead. Turning towards the lane, he paused for a minute; it was still too dark to see beyond the lane

but already he could sense it brooding in the darkness: Bankside Mine Pit, waiting to swallow him up.

The village of Bankside Mine was transforming now as lines of men, women and children took to the cobbled streets, leaving their cottages and making for the dirt road that led to the pit. It was a good two miles’ walking before they would arrive at the yawning entrance hole and many of them looked half asleep. Some of the fathers were carrying sleeping children on their backs, their thumbs in their mouths as they slumbered on. Tim started in surprise as Daisy and Jo pushed past him, jostling for position amongst a noisy group just in front of them. Daisy was thirteen and had worked down the mine since she was nine but, as Mam had said, it would be a big change for her today, too: she was changing jobs from being a trapper, opening and shutting the doors in the mine, to the much harder job of being a hurrier, pulling the corves or coal trucks, loaded with coal, from the coal face to the end of the seam.

Daisy’s round face beamed at the thought of her new job. Her dark hair was smooth and silky and tied at the back by a pretty green ribbon that Mam had bought for her at the fair, and her dimpled cheeks and ready smile gave her a friendly look that made her very popular with the other children. She loved to talk too, a trait that didn’t make her too popular with Mrs Thundertone, the Sunday school teacher. Only last week she’d

been put into the corner with the dunce’s cap on, for talking to Susie Briar during one of Mrs Thundertone’s never-ending talks about SIN and what terrible things would happen if you did a SIN, one of the strict Sunday school teacher’s favourite subjects.

Now she hopped and skipped around the little group, thrilled at the thought that her new job would earn her more money than the other children: that she could lord it over the younger trappy lads and lasses.

“I’ll be waving to the lot of you, stuck in one place, sitting beside your little doors while I’m off doing a proper job.”

“It’s just not that easy, our Daisy,” said Jo, shaking his head like a wise old man. “They’re really heavy, them corves, and you have to move quick you know, or they’ll beat you. Some of them slopes are the very devil to climb and your knees’ll be bleeding before you know it.”

“You always think you can do everything better than me. Well, you’ll find out the hard way.” He was bolder now he was out of Dad’s earshot. Maybe now he’d be able to talk some sense into the girl. At thirteen he’d already been working as a hurrier for a year: the muscles on his chest, and tell-tale bald spot on his head caused by pushing the heavy loads of coal, marked him out as experienced. He rubbed the red angry bald spot. His heads, as he called them, were getting worse. Dad thought it was just an excuse to stay at home, away from the hated pit, but the mild headaches that had started when he began as a hurrier had become steadily worse. Sometimes he saw flashing lights and smelled strange smells just before the pain began, and once it began it was impossible for him to push a loaded corve with his head. He hated Dad thinking he was soft, that he wasn’t hard enough to be proud of. Mam understood and did what she could to defend him when Jay lost his temper.

His feet were hurting already. The boots that Mam had looked out for him had been worn by six other lads before they passed to him. He wasn’t used to the heavy wooden soles, which dragged on the polished cobbles and made his legs feel like lead.

As the group reached the end of the village and headed out across the fields, Tim fell into step with his dad and another man.

“You heard about Pigstone Pit then, Paddy,” said his dad, shaking his head sadly.

“Aye, our Jenny told us about it last night; she’d been over to the town collecting washing from the big house and the women did nothing but talk about it,” the man said, with a heavy sigh. “Biggest blast for a while, blew the whole of the main passage way and the whole of the shaft, folk couldn’t get in or out. They say the fire lasted two days before they could get enough water up to flood the thing and put it out. And old Ma Nicholson, a nasty business and no mistake.” Paddy shook his head solemnly.

“I heard she lost her lads down there,” Jay said, sadly.

“Aye, but that was only the half of it,” the other man continued, heavily. “It weren’t just Jimmy and Simon she lost, though that would have been bad enough. No, she lost her little lad Mark and all; four years old he was, and only his second day in the pit.”

Tim’s heart missed a beat. He wanted to block his ears, not to listen to any more, but he couldn’t help himself.

“Aye, and her girl Nellie, and she was only eight,” he went on.

“My Jenny was talking to a woman who’d been there, at the pit head with Ma Nicholson. She said that one by one they brought them up, all wrapped in sheets. But it didn’t hide much,” he added in a hushed whisper. “You could see how bad they were, from the blood and all, and the terrible smell of burning.”

Tim’s stomach lurched. He couldn’t let the men see him like this; with a single leap he managed to make it into a nearby ditch before the remains of his breakfast re-appeared. The sweat poured down his neck and all he could think of was the dream. The two men carried on talking, so caught up in the bad news that they didn’t notice that Tim had disappeared into the ditch.

“Aye, but that still weren’t the worst of it. It was what happened when they took what was left of poor little Nellie back to her house. They found her mam next morning, sitting beside the coffin, lost her mind they say.”

Tim felt hot tears begin. But he couldn’t cry now: if he cried they’d see, they’d think he was like Jo; soft, not much of a man. But the feelings were strong, too strong to ignore. He couldn’t go on, he couldn’t do it; face the heat, the dirt, the stench, and worse: the creature that crept out of his dream, the creature that waited for him down Bankside Mine Pit.

[1] Northern term meaning brother, sister or child

[2] Slang for potatoes

[3] Slang for mate

Leave a comment